The emergence and spread of antibiotic resistant tuberculosis (TB) has increased during recent years, and a severely affected country is India. In Mumbai, The Mumbai Mission for TB Control initiative was formed to scale up TB care and tackle drug resistance. By involving private practitioners operating in the city's urban slum areas, the initiative is showing results in terms of new case detection, early treatment and increased adherence rates.

The burden of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is one of the top ten most common causes of death worldwide. In 2016, 10.4 million people fell ill with TB and 1.67 million died from the disease, with the number of multidrug-resistant TB cases reaching 490,000. India accounts for over a quarter of all these TB cases and deaths. For drug-resistant infections the treatment options are not as effective, and more often lead to treatment failure.

India’s TB program

All of India’s TB patients are entitled to free treatment and care from the state-sponsored Revised National TB Control Program, which was launched in 1997 and is the world’s largest TB control program. The program has achieved a 55% reduction in TB prevalence rate and a 58% reduction in TB mortality rate between 1990 and 2014.

Despite much progress, India still faces significant challenges with for example diagnosing disease, detecting resistant TB, co-infections with HIV and suboptimal prescribing practices.

One major problem is that new TB patients often end up in the country’s vast and poorly regulated private health sector. This makes it difficult to ensure quality of treatment and follow up of patients.

The Mumbai Mission for TB Control

The Mumbai Mission for TB Control (MMTBC) was formed in response to a growing concern over the spread of TB and increasing incidence of drug-resistant TB in the city. MMTBC has been operational since mid 2014 and brings together civil society actors with local and national authorities to improve TB care and effectively tackle drug resistance in low resource settings. An important component is to engage the private health sector to improve access to TB services.

Improving TB care by engaging the private health sector

A Private Provider Interface Agency (PPIA) has been set up as part of the Mumbai Mission for TB Control to network private-sector physicians, pharmacists, laboratories, and hospitals. The PPIA is implemented by PATH, a US-based international nonprofit organization that has been working in India for more than three decades to improve health by collaboration and innovation.

Private providers/physicians, from both the formal and informal sectors, are linked through PPIA field officers to nearby x-ray and sputum-testing facilities. Patients with TB symptoms are given vouchers for a free digital chest X-ray at these diagnostic facilities. If TB is suspected based on the X-ray, the patient is referred to an experienced chest physicians at a hub hospital, who then provides specialized testing and care. Confirmatory diagnosis and drug sensitivity test is made via GeneXpert®, a fast test endorsed by the WHO that is also free service under the program. Once TB is confirmed, vouchers allow for free anti-TB medicine from private pharmacists. Reimbursements for notifications and subsidized care are paid to providers and diagnostic centers.

Using the M-Health approach

A significant feature of the Mumbai Mission for TB Control initiative is its ‘M-Health’ approach, making creative use of mobile phone services to deliver healthcare. For example, after the patients have been diagnosed with tuberculosis, they can receive an electronic voucher for medications that they can redeem at no cost from private pharmacists. Patients also receive reminders to treatment adherence by mobile phones.

Encouraging results on engagement and diagnosis

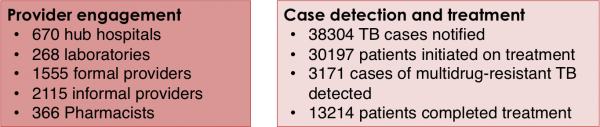

As of October 2017, the PPIA is working in 670 hub centers in 24 wards of Mumbai, and has engaged more than 2115 traditional medical physicians working in the slums of Mumbai. Furthermore, 1555 qualified physicians are working at 670 hospitals and clinics. Physicians in their networks have initiated treatment of 30,197 tuberculosis patients, of whom 13,214 completed the treatment. Over 3000 patients have been notified being infected with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and been referred to treatment.

Reducing inappropriate antibiotic use

Tuberculosis treatment involves therapy with multiple antibiotics for at least six months. Resistance development in TB is fuelled by the use of wrong drugs or dosages, wrong combination of drugs, poor quality medicines, and poor adherence to treatment among patients.

Given that many of the early symptoms of TB are common to a range of respiratory illnesses, it is not surprising that in the absence of accurate diagnosis, there is a considerable amount of inappropriate use of antibiotics. For example, a study of the antibiotic dispensing practices in Indian pharmacies found that patients with tuberculosis symptoms were often provided with broad-spectrum antibiotics, instead of being referred to a health care provider.

Concluding remarks

Initiatives such as the Mumbai Mission for TB Control that focuses on early detection and timely treatment of tuberculosis in a country like India could have a significant impact on reduction in misuse of antibiotics and bring about an overall reduction in antibiotic resistance. It also offers a healthcare structure that may be possible to utilize in the work to improve use of antibiotics for other types of infections.

Selected Resources

| Resource | Description |

| Improving Tuberculosis Services in Mumbai: PATH Connects With Private Providers to Improve TB Care for Urban Populations at High Risk | Fact sheet that describes PATH’s collaboration with community-based organizations in Mumbai to develop a comprehensive urban TB service delivery model; the Private Provider Interface Agency (PPIA). |