2021-06-03

Antibiotic resistance is one of the most pressing public health problems of our time. It causes hundreds of thousands of deaths each year, affects many people’s livelihoods and is threatening to undo the advances of modern medicine. Without effective antibiotics, it would for example be too risky to conduct organ transplants, routine surgical procedures and cancer chemotherapy. Global development would also be severely affected.

Antibiotic resistance is a global development issue

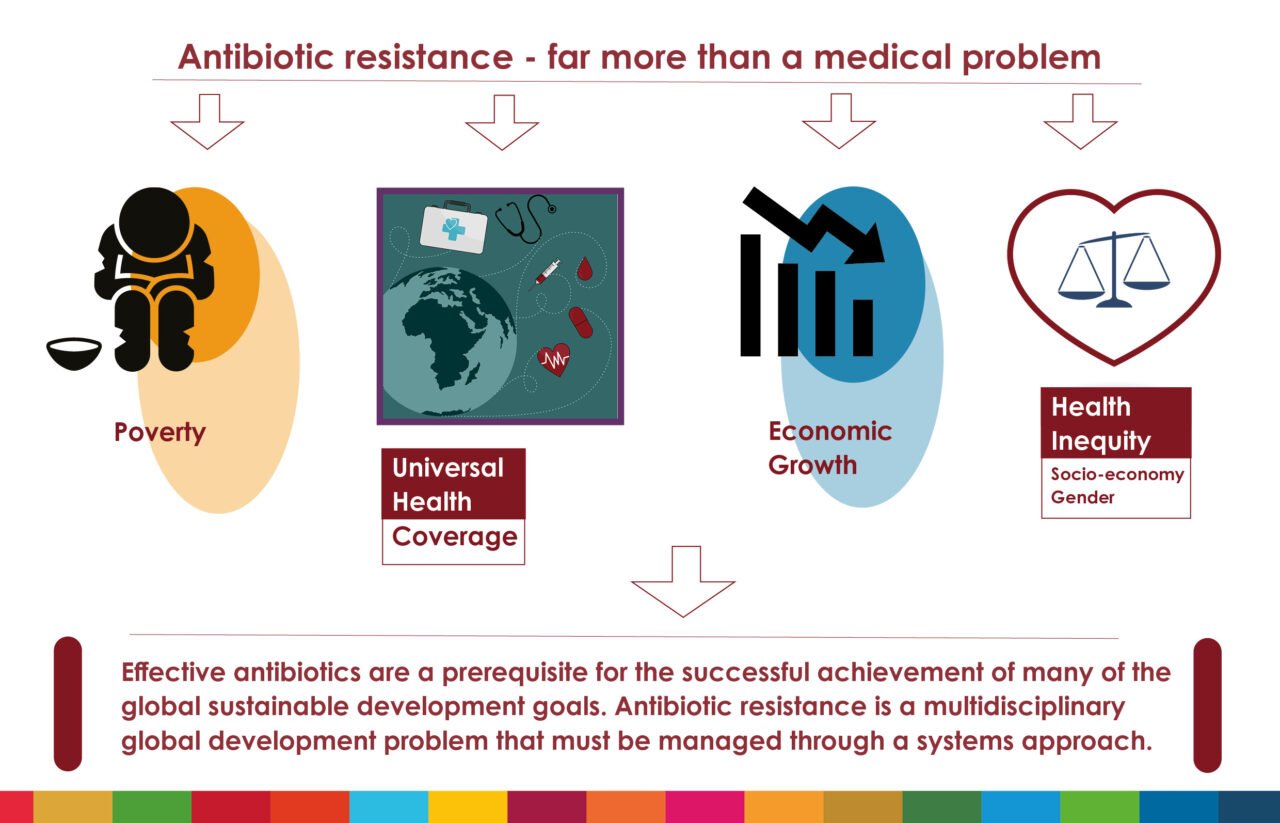

Antibiotic resistance is often wrongfully depicted as purely a medical problem, presumably because of the direct and devastating consequences that patients with resistant infections may experience. Such narrow perspective prevents the issue from being recognized as a systems failure and from getting the broad political attention it requires. In fact, having effective antibiotics is a prerequisite for the successful achievement of many of the global sustainable development goals (SDGs) specified in Agenda 2030.

In addition to affecting SDG 3 – good health and well-being, antibiotic resistance negatively impacts for example:

- SDG 1 – no poverty

- SDG 2 – zero hunger

- SDG 5 and 10 – gender equality and reduced inequalities and

- SDG 8 and 12 – decent work and economic growth and responsible consumption and production.

In other words – antibiotic resistance is a multidisciplinary global development problem that must be tackled systematically.

The varying burden of antibiotic resistance – an indicator of health inequity?

Antibiotic resistance occurs in all countries, but its prevalence differs geographically as well as between population groups. An overall lack of data globally means it is more or less impossible to compare national situations, but there is consensus that antibiotic resistance disproportionately affects low- and middle-income countries where the infectious disease burden is largest and the health care and agricultural systems are weaker. Despite the fragmented global resistance data, some studies have indeed found an association between higher prevalence of resistant bacteria and lower gross national income – possibly because lower national income could be indicative of circumstances that favors spread of resistance. Poorer water, sanitation and hygiene and poorer governance (such as corruption) are some examples of other factors that have been associated with higher resistance levels.

Resistance levels do not only differ between countries, but also vary within populations. Factors like gender and socio-economic status may impact individuals’ exposure to environments and circumstances that favor selection or spread of resistant bacteria. Gender could for example influence the kind of work people do, the exposure to animals and one’s health care-seeking behavior. Biological differences between men and women may also predispose individuals to certain infections, like urinary tract infections which are far more common in women. Both gender norms and sex thereby impact individuals’ risk of and response to infection, which in turn affect antibiotic use patterns and antibiotic resistance levels. Altogether, this means that antibiotic resistance can shine a light on health inequities on macro as well as micro level.

The World Health Organization describes equity as:

“the absence of avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically”.

Therefore, health inequities (…)

”also entail a failure to avoid or overcome inequalities that infringe on fairness and human rights norms”.

Antibiotic resistance drives poverty

Antibiotic resistance is costly both for the individual and for society and can accelerate economic segregation and increase inequalities. Second- and third-line antibiotics are generally more expensive than first-line alternatives, which means that patients who pay out-of-pocket for health care services must pay more to treat a resistant infection than a susceptible one. In addition, resistant infections generally take longer time to treat and do to a higher degree require hospitalization. These factors contribute to the increased cost levels, which threatens to push economically disadvantaged individuals and households into poverty.

In fact, the median overall extra cost to treat a resistant bacterial infection has been estimated to correspond to the wage earned by a rural male casual worker in India during 442 days of work. A World Bank report from 2017 estimated that in a high-impact scenario, antimicrobial resistance (i.e. resistance to antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals and anti-parasitic agents) could push an additional 24 million people into extreme poverty by 2030. Resistance is costly also from a societal level. For example, infections that are more difficult to treat lead to longer absence from work which affects both household incomes and labour market outcomes. In the long run, this impacts the economy of countries.

Poverty drives antibiotic resistance

People who already live in poverty are less able to prevent and respond to infectious diseases as they more often lack safe water and sanitation facilities and access to health care. That is, one’s living and housing conditions may impact both the risk of falling ill and the chances of getting well.

There are at least two billion people globally using a drinking water source contaminated with feces and two billion lack access to basic sanitary facilities like toilets and latrines. This means that a lot of people, 673 million, still defecate in the open. These are a some of the circumstances that facilitate accelerated spread of bacterial infections, including resistant ones, which in turn increases the need for antibiotic treatment.

The global community needs to ensure universal access to essential health services

To have living standards that secure one’s health and well-being is a fundamental human right specified in article 25 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Importantly, this includes access to adequate medical care. Yet, over 70 years after the human rights declaration was published, half of the world’s population still lack access to essential health services, including affordable essential medicines and vaccines. In fact, lack of access to antibiotics still causes more deaths than antibiotic resistance itself, even if this may change with rising resistance levels. There are also a lot of improvements to be done regarding the distribution and use of vaccines worldwide. Over 800.000 children under five died from pneumonia in 2017. The existing pneumococcal conjugate vaccine has the potential to save the lives of many children, as well as to avert over 11 million days of antibiotics every year. Still, the global third dose coverage for the pneumococcal vaccine was estimated to be just 48% in 2019.

Short interview with Dr. Evelyn Wesangula, National Focal Point for AMR, Kenya, on the importance of antimicrobial resistance and universal health coverage and its impact on the development agenda in countries.

The world still has a long way to go in ensuring equal, affordable and timely access to essential medicines, vaccines and health care equipment for all patients in all countries. This has also been clearly demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. As of March 2021, vaccine nationalism had resulted in high-income countries buying over 50 % of the vaccine doses, although they are home to less than 20% of the global adult population. The decision from the US to support a proposal from South Africa and India for a temporary waiver of patents from COVID-19 vaccines was therefore very welcome, and it reaffirms the important notion that public health should override intellectual property rights. A similar approach needs to be taken in other relevant fields where there is a great unmet public health need. This includes the field of antibiotic research and development where no new class of drugs has been developed in over 3 decades, despite the rising levels of antibiotic resistance globally.

No universal health coverage without effective antibiotics

To succeed with the mission of reaching target 3.8 of SDG 3, achieve universal health coverage for all, it is a necessity to address and manage antibiotic resistance. Good quality health care cannot be delivered unless it is possible to treat bacterial infections, and it will be very difficult to achieve sustainable financing of universal health coverage unless antibiotic resistance is appropriately addressed. The World Bank has estimated that antimicrobial resistance, if left unchecked, could cause a drop of up to 3.8% of the global gross domestic product (GDP) by 2050. Although this estimation also takes resistance to antifungals, antivirals and anti-parasitic agents into account, it gives a hint of the enormous economic consequences that will follow unless the global, regional and national responses to antibiotic resistance are proportional to the problem it constitutes. We cannot afford inaction. Lives and global development are at stake.

4 take-away messages

- Antibiotic resistance needs to be viewed and handled as the global development issue it is.

- Both political and medical discussions on antibiotic resistance need to take social determinants of health like gender and socio-economic status into account as this is a prerequisite for obtaining health equity.

- Access to essential health services and medicines is nothing else than a human rights issue and must be handled accordingly.

- Work on antibiotic resistance need to be prioritized on all levels as it is a prerequisite for successful achievement of many of the SDGs, including target 3.8 on universal health coverage. Universal health coverage is in turn a prerequisite for achieving health equity.

This year ReAct is celebrating 15 years of action on antibiotic resistance and this theme article is part of the celebration!

This year ReAct is celebrating 15 years of action on antibiotic resistance and this theme article is part of the celebration!

The story of ReAct started 15 years ago with a small group of people, many who are still with the network today. They all shared a passion for global health, and felt the urgency to address the growing problem of antibiotic resistance. The network has since grown, with the presence of offices in 5 continents and many passionate members working together.

Read more about ReAct 15 years celebrations and learn more about the story of ReAct!

Additional references article: Antibiotic resistance – far more than a medical problem

The varying burden of antibiotic resistance – an indicator of health inequity?

- Journal article. Alvarez-Uria et al. Poverty and prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in invasive isolates.

- Journal article. Savoldi et al. Gross national income and antibiotic resistance in invasive isolates: analysis of the top-ranked antibiotic-resistant bacteria on the 2017 WHO priority list. (not open access)

- Aarestrup and van Bunnik. Comment on: Gross national income and antibiotic resistance in invasive isolates: analysis of the top-ranked antibiotic-resistant bacteria on the 2017 WHO priority list (not open access).

- Savoldi et al. Gross national income and antibiotic resistance in invasive isolates: analysis of the top-ranked antibiotic-resistant bacteria on the 2017 WHO priority list—authors’ response (not open access).

- Collignon et al. Anthropological and socioeconomic factors contributing to global antimicrobial resistance: a univariate and multivariable analysis.

Antibiotic resistance drives poverty

- Cecchini et al. Antimicrobial Resistance in G7 countries and beyond: Economic Issues, Policies and Options for Action (PDF).

- Chandy et al. High cost burden and health consequences of antibiotic resistance: the price to pay.

The global community needs to ensure universal access to essential health services

- Laxminarayan et al. Access to effective antimicrobials: a worldwide challenge.

More news and opinion

- Winners ReAct Asia Pacific and Aspic Clubs photo competition 2021

- ReAct Africa Conference: Key takeaways and way forward

- World Health Assembly Special Session 2: Openings for stronger governance of the silent antibiotic resistance pandemic

- Staff interview Juan-Carlos Lopez

- ReAct highlights during World Antibiotic Awareness week 2021

- Staff interview Maria Pränting

- 5 lessons learned from Latin American Summit: Community empowerment – vital for tackling AMR

- The WHA74 Special Session on Pandemic Preparedness and Response – an opportunity to address antibiotic resistance

- ReAct announces the top 15 teams to participate in the online global design sprint Innovate4Health 2021

- City of Hyderabad joins ‘Go Blue’ campaign as part of WAAW Activities

- ReAct Europe and Uppsala University go blue to shed light on the antibiotic resistance issue

- Could the best chemotherapy be an antimicrobial drug?

- Press release: Unique collaboration between Ministry of Health, Zambia and ReAct Africa

- Mobilizing communities to act on antibiotic resistance

- ReAct activities for World Antimicrobial Awareness Week 2021

- Dr Vijay Yeldandi

- 4-day Summit: Latin America discusses the role of the community in National Action Plans on AMR

- The world needs new antibiotics – so why aren’t they developed?

- 3 ways the new WHO costing & budgeting tool supports AMR National Action Plan work

- 5 years after the UN Political Declaration on AMR – where are we now?

- Víctor Orellana

- Local production of vaccines and medicines in focus: Key points from ReAct and South Center UN HLPF side-event

- Behavior change to manage antimicrobial resistance: 8 briefs and 1 webinar-launch by Uppsala Health Summit

- ReAct and ICARS to develop policy guides and tools for low resource settings

- Tapiwa Kujinga, Director of PATAM: In Zimbabwe civil society is involved in every aspect of the response to AMR

- COVID-19: India pays a high price for indiscriminate drug use

- Lancet Global Health article release: Resetting the agenda for antibiotic resistance

- 3 key takeaways for AMR from this year’s World Health Assembly WHA74

- Antibiotic resistance – far more than a medical problem

- UN High-level Dialogue on AMR: political will and investments needed

- Resetting the agenda for antibiotic resistance through a health systems perspective

- 3 questions to newly appointed STAG-AMR members Otridah Kapona and Sujith Chandy

- Walk the talk: time is ticking for all to act on antibiotic resistance!

- Vanessa Carter: 3 years of surviving a drug-resistant infection made me want to create change

- Upcoming ReAct Webinar: Expert Conversation about new report

- ReAct report: Governments need to take more leadership to ensure global sustainable access to effective antibiotics

- 4 considerations for addressing antimicrobial resistance through pandemic preparedness

- Preventing the next pandemic: Addressing antibiotic resistance

- 4 key takeaways from the virtual ReAct Africa Conference 2020

- The threat of the unknown: is lack of global burden data slowing down work on antibiotic resistance?

- ReAct input to the WHO Executive Board Session on Antimicrobial Resistance

- Dr Gautham: informal health providers key to reducing antibiotic use in rural India